The Oasis of Dreams: Re-greening the Desert of Djibouti

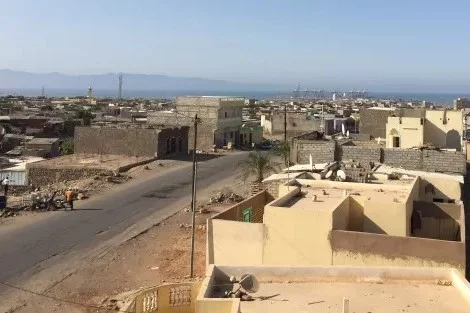

Ali Omar remembers the time when the barren desert in northern Djibouti, which he considers his home, was a bustling coastal resort surrounded by water on all sides and teeming with fish. The 75-year-old reminisces about his hometown in the 1970s, saying, “Many people lived here and had shops along the beach.” The weather was hot year-round, and the village dwindled to a few huts in the desert.

“I needed a jacket to live here,” he says, gazing at the beautiful morning sun by the beach, which is now devoid of the crabs that used to roam inside and outside the shore. There was enough fresh water for everyone and plenty of seafood, such as crabs and various fish, which were transported by planes to the capital.

“Then the problems started,” says Omar. The rising sea level began to form sandbanks that blocked the channel that supplied oxygen-rich seawater to the mangrove forests, providing a fertile ground for fish and crabs. When the trees withered and died, their fallen trunks choked the forest.

Mohamed Omar, who manages a small eco-hotel near the mangrove trees, says, “There were dead trees everywhere inside the forest, preventing the remaining trees from getting the oxygen-rich water they needed.” He adds, “Mangrove trees need mud to grow, but the sand intrusion choked them, and the water turned stagnant due to the lack of saltwater that the mangrove trees need. Many mangrove trees died, and the fish disappeared.”

As the fishing-related business declined and the freshwater supply dried up, people who had lived in the desert for generations began to migrate from the area. Those who remained had to pay for fuel to operate power generators to pump fresh water from the ground – water that became difficult to access due to the intrusion of saltwater into the groundwater or pay for water trucks coming from the nearest city.

Globally, rising sea levels, temperatures, unpredictable rainfall, and deforestation are increasingly damaging fragile coastal ecosystems and putting people in already vulnerable and poor countries like Djibouti at the forefront of the battle against climate change.

Dr. Ahmed Ahmed Jibril, a climate change adaptation specialist working at the Ministry of Environment in Djibouti, says, “Khor Angar is the largest mangrove forest in Djibouti and the most important. It used to cover an area of 120 hectares, but it has decreased to 60 hectares.” “To ensure its survival, we had to intervene.”

To save this important ecosystem and the people who depend on it from any negative impact, the government of Djibouti, the United Nations Environment Programme, and partners have helped the local community restore critical areas, clear and dredge channels, and improve water supplies.

With funding of over $2 million from the Global Environment Facility, the project supported the restoration of mangrove forests to provide a barrier to protect the fragile ecosystems and important local communities from seawater intrusion. The community cleared the debris that was blocking the forest, and mechanical excavators were brought in to remove large pieces and clear sand from the seawater channels. When the water is recycled, the forest will be able to breathe and grow again.

New generations of mangrove trees now thrive on the beach in the fenced-off area outside the village to prevent camels – the only animals that can survive here due to the lack of grazing land – from eating the plants.

Khor Angar nurseries now produce around 35,000 seedlings annually, and the community has planted over 100,000 seedlings in total, according to Jibril, who oversaw this pioneering project. He adds, “The most important thing for us is to ensure that the community that relies on these mangrove trees can live and sustain their livelihoods from them.”

It will take between 50 and 100 years to fully restore the mangrove forests, but the community is already witnessing results, with the return of crabs to the area being one of the most notable. Ali Omar explains, “Things are improving, little by little.” The goal is to achieve natural regeneration resulting from the project’s success, with a mortality rate for trees replanted in the mangrove forests of only 0.5 percent.

The project has also helped fishing communities overcome declining fish stocks by providing better equipment and training on sustainable fishing practices, planting date palms, promoting ecotourism, and supporting small-scale agriculture. It has also helped people access better and cheaper freshwater by upgrading the desalination system with a new pump, pipes, and generators.

Khor Angar is one of the sites in Djibouti where the project has helped communities adapt to climate change, recurring droughts, and erratic rainfall. In the southern region of Djibouti called Damerjog, the project built three small dams to improve agriculture and prevent saltwater intrusion into wells, and it supported the installation of solar-powered irrigation in 18 farms.

In addition to the inland areas of Khawr Anjir, the United Nations Environment Programme and its partners supported the establishment of a small tree nursery to plant palm trees for shade and fruit, and to test whether it is possible to successfully rehabilitate desert areas. Ali Ibrahim Mohammed, 65 years old, who has witnessed the weather changing, says: “There used to be a lot of forests here to the point that you couldn’t see if people were passing by or not.”

He adds: “When I was young, rain used to fall every season, and in the past ten years, it no longer rains at all.” “Without trees, there is no rain, and without rain, there is nothing.”

Mohammed hopes that a group of palm trees planted in 2014 will remain, and that the reforestation initiative will be expanded to ensure the survival of people living in the surrounding areas.

Abdul Mohammed Omar still walks two kilometers a day to guard and water the trees, even though he no longer receives payment for doing so. “I work for my country and the community,” he says, adding that he dreams of the day when the trees will bear fruit and provide large areas of green trees and shade in the desert of Djibouti.

Algeria

Algeria Bahrain

Bahrain Comoros

Comoros Djibouti

Djibouti Egypt

Egypt Iraq

Iraq Jordan

Jordan Kuwait

Kuwait Lebanon

Lebanon Libya

Libya Mauritania

Mauritania Morocco

Morocco Oman

Oman Palestine

Palestine Qatar

Qatar Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia Somalia

Somalia Sudan

Sudan Syria

Syria Tunisia

Tunisia UAE

UAE Yemen

Yemen